Henry Willis refused to swear the Oath of Allegiance to King Charles II when he became a Quaker and so joined other prisoners of conscience in a cell not far from the

Tower of London. Upon his release, he and his family,

believing they could worship in the New World

unencumbered, set sail across the Atlantic, in 1675.

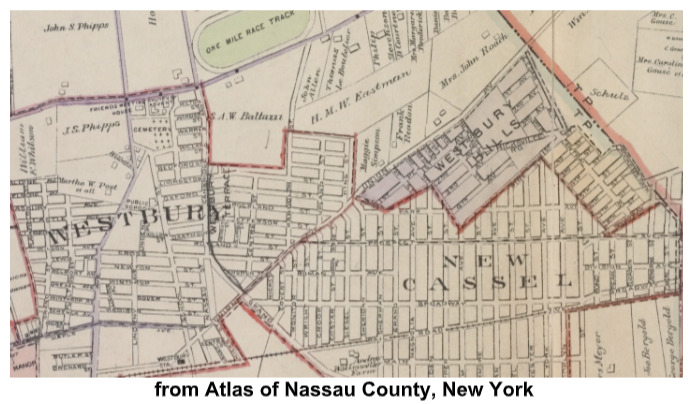

Upon his arrival in America, Willis purchased 22 acres

from John Seaman, where the hilly woodlands of Long

Island meet the outwash plains, near where my suburban

house would be built, in 1951.

The Willis family were farmers who pastured their

livestock on the Hempstead commons shared by English

dissenters and Dutch settlers alike.

There were horses on Long Island when Henry, his wife

and eight children arrived to establish their lives in the New

World. For ten years prior to the Willis’s arrival, English

administrators, soldiers and colonists were betting on races

at the Newmarket Course in Hempstead.

The date of the arrival of first enslaved people in

Westbury is unknown. What is established is that slavey

came to New Netherlands in 1626 and Long Island was the

leading slave-holding region in the New York province.

Nearly every farm on the island had an enslaved person for

more than a century.

Quakers began emancipation before the Revolution.

The 1775 census listed only one male slave in Westbury. It

also noted that “there is sundry free Negroes Melattoes and

Mustees Residing within ye Township of Oysterbay that

may probably Be Likely In case of Insurrections To be as

Mischevious as ye Slaves.”

Records show John Willis, junior, and Elizabeth Titus

lived in Westbury, as free blacks, presumably manumitted

by the Willis and Titus families.

Two and a half centuries after their arrival, where the

Willis homestead once stood, would be stables housing

thoroughbreds. Some of their descendants would be

counted amongst those living in aristocratic splendor on

estates carved out of the woodlands. On the sandy plains

first would appear potato farms, then thousands of houses

constructed in quick order to become America’s first suburb.

Their slave-holding Quaker descendants would institute

voluntary emancipation, then some the war to enforce

abolition everywhere. Some the formerly enslaved people

would build their own communities and establish their own

churches.

The native people are long gone. The theft of their land is

rarely recalled and the massacre during Kieft’s War is an

obscure footnote, a fact not even taught in the school that

occupies the grounds of the slaughter.

The colonial road that ran from Jamaica to Jericho is a

six-lane roadway. All that remains of the greatest plains

east of the Mississippi where farmers for centuries brought

their livestock to graze on treeless ground is a handful of

acres behind a fence, wedged between a parkway, a feeder

road, a college campus and a crumbling airplane runway.

In this book are stories about my neighborhood, a

fictionalized memoir of sorts, sketches from historical

records, personal experience and imagination.

No trace of Indian lives

Can be found among the houses,

Not an arrow has been uncovered

Even while digging for suburbia.

Of course there are no headstones

But neither are there tools nor bones

Worthy of consideration.

Many crossed the broad water,

Fished the salty seas,

Trapped small game

In the woods north of here.

If they crossed this country,

They took their traces with them,

Holding their lives in their quivers,

Packing their shadows as they went.

On this earth we grow berries and asparagus;

Now beans and grapes grow full.

Massapequa, look for me in my dreams.

Tell me the secret of this forbidden place.